This was how I thought it should be. It was also how I feared it was.

In the immediate moment though my biggest fear was having to go into that putrid bathroom to switch out of my sweaty clothes. Since when are toilet hut cleaner people non-essential? Holy stench.

Fall's chill was in the air this morning as I pedaled along the Susukigawa River. The low-hanging clouds to the west were so thick you wouldn’t know there were any mountains out there. To the south, over the Kiso Valley and maybe as close as Shiojiri, the grays gave way to a swath of blue sky that offered hope but nothing you could call promise.Two hours, thirty-five road kilometers and

seven hundred vertical meters later I was rolling, sweaty and excited, into the Mitsumata parking lot and the gateway to Mt. Jonen.

I’d biked up here a few weeks prior. The place was utterly deserted. So was the hut at the trail head, at the far end of a rocky access road, where there were signs asking anyone who had come this far to please turn around and go home – and oh by the way watch out for bears.

This morning the parking lot was packed, mostly with cars from out of the area. The two auxiliary lots further away had looked pretty full too as I rode by them. Evidently these mountains were now crawling with people. This was both good and bad. People are generally safer than bears, but on a hike in the wilderness I almost prefer bears.

My bear-related fears now (presumably) gone with the hordes, I had only the minor concerns of weather and time. (I didn't have a trail map, nor did I have any clue how strenuous the hike ahead of me would actually be, but for me such things don't rise to the level of 'concern'.)

Outside the hut at the trail head three men were helping people fill in their 'tozan todoke' - little forms with the info necessary to identify who got eaten by a bear. They couldn't have looked any more excited to talk to me, if for no other reason than the pleasure of listening to the gaijin's Japanese.

“Doko made ikimasu ka?” asks the guy in the middle.

“I want to do the Jonen-Cho Loop,”

I say, wondering, as I often do, how bad my Japanese accent really is.

”Ii ne! Sou suru hito ga ooi ne!”

I scan the massive trail map behind them.

“According to that it takes about fifteen hours,” I say, pointing.

“Sou da yo ne...” Either they didn’t get my

Japanese or they’d been wearing masks at altitude for too long and weren't tuned into the mortal visions floating into my head.

“It’s already 8:20,” I say, as if they

might not be aware.

One of them checks his watch. “Sou da ne. Jikanteki

ni muzukasii kamo ne.”

Yes, 8:20 plus fifteen hours means not

good.

“Rampu wa aru?”

“Yes, I have a light.”

“Do you have rain jacket?” one of them

asks in English, smiling and gesturing like he's pulling a blanket over his head.

“Motte imasu yo,” I reply.

Then one of them, oddly, asked if I’d come here by bicycle.

“Muri shinaide ne,” he said, pointing to

his chest – basically telling me not to overdo it and end up having a heart attack.

Then he added: “Tozan hoken wa arimasu ka?”

No, I didn’t have any mountain climbing

insurance. Nor was I worried about dying in any way, not with all these people scaring off all the bears. I bid my three friends farewell and took off on a jog across the grass, up to the entrance to the trail.

I have a few reasons for running when I am in the mountains. For one, I love the simple act of climbing, of throwing myself into the mountains, and running somehow intensifies that feeling. I also think I’m trying to prove something to myself, trying to keep in shape as if I can fend off the inevitable advance of the years. Then there’s the fact that eight-twenty plus fifteen, or even ten, equals dark.

I had no illusions about running the whole way up and across and down, but I figured the first half hour or so might be doable.

The trail had other ideas.

The terrain was surprisingly rocky, not like a mountain so much as what I imagine is left after the controlled demolition of a building full of dirt. Massive tree root systems stood like meter-high retaining walls keeping the trail from being washed away with all the rain. And it had in fact been raining. The air was still swirling with mist. Nothing underfoot was dry.

Slick roots and wet rock faces. Muddy, slippery

inclines. Loads of fun, really.

I toyed with the idea of going back and hanging with my friends at the hut.

I spent most of the climb scrambling up rocks and navigating the Jurassic tree roots in my way, all the while reminding myself that wiping out and breaking my ankle would be bad. Sprinkled in were quick moments of running the semi-flat stretches, and slow moments of passing people with heavy-looking packs and heavy-sounding breath. They all, it seemed, were geared up to spend a night or two in the mountains - which might increase one's chances of seeing a bear though I think most people simply want to see the sunset. And not have a heart attack.

I kept looking for chances to run, even

just for a few steps. The old mossy forest, wet and cool and misty, was fairytale beautiful (albeit a Grimm Brothers fairytale). But if the way down was anything like this I was going to have to take it super slow so I wouldn't slip and break something. This could very well mean hiking long past sunset but hey, with a light and without mountain

insurance (whatever that even was), dark would be preferable to broken.

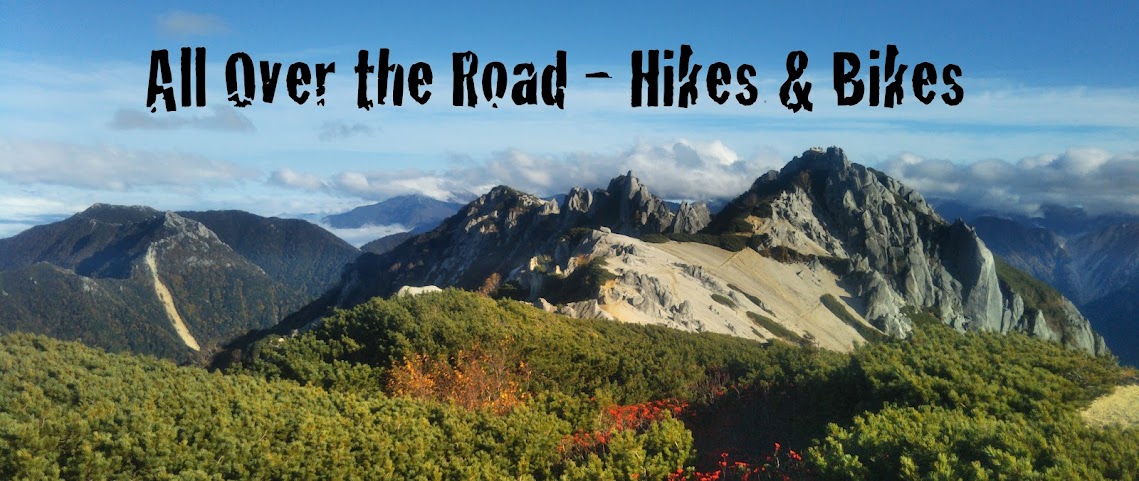

The mist thickened and dissipated, with some rainfall in the middle. Then, for the first time since riding along the Susuki River three or four hours ago, I caught a glimpse of blue sky. Through the trees a rounded peak appeared; a false peak, no doubt, but a peak, covered with shrubby foliage and littered with big white boulders. The trees gave way and the view opened up. Further off and up above I could pick out the top of Jonen-dake, playing hide and seek with me amid the swirling white clouds.

From a distance Jonen-dake looks like a pyramid. There is, however, a ridge that runs east from the main peak. The highpoint of this ridge is Mae-Jonen-dake.

For a minute it was right in front of me. Then the trail ran left, leading across the whitened rocks to the south face of the summit where, quite suddenly, the peaks of the Hotaka range came into view.

These peaks are not visible from town. You have to make the trek up here if you want to see them. Or you can take a bus up to Kamikochi and walk for ten minutes but where’s the satisfaction in that? Then again the bus driver probably doesn't ask if you have tozan hoken.

Most of the Hotaka range - and most of the rest of the world - sat hidden behind the clouds. But I don’t think

that took away from my wonder at it all one bit. I was out there, up above the

clouds covering my town and my house, looking across at peaks 10,000 feet high, backed by that sapphire blue heaven.

This isn't what I come up here for. Not exactly. It's what this gives me that is the ultimate prize; something intangible that defies explanation but is shared, to varying degrees, by the others who make the hike up here - or up anywhere.

The trail turned right and ran up the steep southern slope of Mae-Jonen. Countless boulders sat among criss-crossing paths running through a sea of low-lying pine brush. Unlike down below, the dirt up here was dry and crumbly. It was hard to walk without sending mini avalanches of earth and pebbles downslope with every step.

As I sent another stream of debris rolling downhill I wondered if that climbing insurance covered people knocked off the mountain by the landslides I was creating.

“Raicho ita,” he said to me.

Ah! The elusive rock ptarmigan! It's a great bonus to see one out here. I scanned the terrain below us but those birds are hard to spot even close up. I kept climbing, preferring to see the trail going down the mountain later than a faint glimpse of a skittish bird now.

From atop this mountain of massive boulders and dwarf pine was an unobstructed view in every direction. To the north and northwest a series of brown peaks ran off into the horizon; one was Tsubakuro-dake, one of the only other mountains around here I've managed to climb since moving here six years ago. To the south and southwest clouds swirled up from the lowlands, obscuring all but the tips of the Hotaka range. The view of the east was like looking out the window of an airplane: nothing but an ocean of clouds.

And right in front of me, directly west, was triangular Jonen-dake.

The path snaked along the ridge, slowly rising, and as I rounded a wall of boulders I almost stepped on a ptarmigan.

He or she didn't fly away in a frantic burst of feathers. The thing didn't even run, it just waddled away from me, disappearing behind some rocks before poking its head out of the pine brush off to the side of the trail up ahead.

He or she didn't seem bothered as I stepped easily, quietly along, closer and closer until I'd drawn even with its not-so-hidden hiding place. I wished I had a zoom lens like a rocket launcher. Or a water gun even. The Japanese Rock Ptarmigan is not just elusive. These birds are a natural monument, a nationally protected species that has found its way onto the endangered list.

I said thanks and goodbye to my feathered friend and looked up to see, piercing the brilliant blue sky from behind Jonen, the iconic, unmistakable pointed peak of Yari-ga-dake.

At 3,180 meters Yari-ga-dake is Japan's fifth highest peak. It is visible from the area where I live. On any fairly clear day its pointed summit peeks out from behind Jonen's south side, twenty miles away. Now here was Yari only five miles from where I stood - yet somehow it seemed no closer.

This would magically change as the valley between Jonen and Yari opened up into full view.

For the first time in two and a half hours the trail split. Downhill to the right was Jonen-goya, one of the many lodges in these mountains that get so crowded in summer that people end up sharing six-foot by three-foot straw tatami mats with complete strangers. (Strangers not for long, I'd say.) Up to the left, the top of Jonen awaited.

Somewhere behind me was Mae-Jonen. If there was a sign marking the actual peak I missed it.

According to that map at the trail head, the hike up to the summit of Jonen was supposed to take something like six hours. I made it in a little over two and a half. The clouds and the mist swirling through the forest lower down the mountains seemed a distant memory under that endless, impeccable blue heaven. I was dry again after getting drizzled on down below. Forget about bears, I hadn't even seen any bear poop. And finally, after years of gazing longingly at this triangular peak from the invisible ligatures of home, I'd made it to the top of 2,857-meter Jonen-dake, entirely under my own power.

It was strangely anti-climactic.

I was standing 2,200 meters above my home - well over a mile. The view to the west could not have been more spectacular. The sea of clouds to the east was no less dramatic a scene. I had reached the highest point of the day, and had more than enough daylight and gas in my legs to complete the loop and maybe even make it all the way home before dark.

But from here...with the world spread out into infinity all around...

There was still so, so much more to see.

I wished I had a huge pack on my back. I'd share a tatami mat with a stranger if it meant more time out here. My family could live without me for a few extra days. They might actually prefer it that way.

For now I'd have to settle for lunch with a view.

Looking south it's not hard to spot the trail for Cho-ga-take. What is hard is believing that it's supposed to take four hours to get there.

The south face of Mae-Jonen had been an obstacle course of boulders and pine brush and loose, gravely dirt. The south face of Jonen would prove similar, except now I'd have the forces of gravity helping me along - whether I liked it or not.

The clouds to the east still swirled, thick and uneasy. I was in no rush to head back down into them. But despite having put the day's highest point behind me I still had more than half of the loop to go. And I couldn't shake my vague fears that the trail from Cho-ga-take back down to Mitsumata would be just like the one going up Jonen.

Ah well...

Despite all the crab-walking and slow-stepping over the boulders, all the scree fields and the sudden drop-offs, I thought I was descending at a pretty decent clip. After forty minutes I turned around.

That's it? That's as far as I've gotten?

The trail led relentlessly downward. Soon I'd be back in the shade - and probably mud - of the forest.

Yet it was here I could finally run uninterrupted for a while. Okay, I could stutter-step for a fifteen minutes. Then I hit the muddy bottom. Then came more rocks and roots on the way back up through the trees. My thoughts drifted back to those things I couldn't control: the length of the trail and the passage of time. And the wanderings of bears.

Without warning the trail spit me out onto this unassuming hilltop. The sign, maybe some kid's Eagle Scout project, read 'Cho-ga-take'.

Really?

If this was Cho-ga-take then I'd be back at my bicycle by 2:00 easy. That is, if I could find the trail leading back to my bicycle. Our little Eagle Scout wannabe, it seemed, forgot to include that part.

Hey wait, what's that little red triangle on the side of the sign? Looks like an arrow, almost. Pointing that way. Towards...oh.

More downhill running, more rock-hopping through the forest...

...and up again, back above tree line, in view of Heaven on Earth and Oku-Hotaka-dake (left), Japan's third highest peak.

More incomprehensible than any of that is how I thought that little hill in the foreground was Cho-ga-take.

As an encore, a few minutes later I wrongly thought for a second time that I was standing on top of Cho-ga-take.

But nope. This was Cho-yari, a pointy peak that juts up from the long ridge that basically makes up the expansive upper reaches of Cho-ga-take. I figured that out a few minutes later when I came across this sign telling me Cho-ga-take was still that-a-way.

Not sure what that blurry blue thing in the corner of the picture is.

By now I'm wondering if I'm going to ever find Cho-ga-take. How do you not find a mountain? If I were down in a valley somewhere the situation might be a bit more concerning. Up here, I found it hard to care all that much. Trust in the signs and your sense of direction, such that it may be. And wherever you can, run.

As the only idiot running along the path, I passed several people who were walking slowly along under heavy packs; laboring, it seemed, like mules. Up ahead I could see the lodge and, just beyond, what was, I absolutely sure, the summit of Cho-ga-take. The sun was high in the sky. The heavens were smiling gently down, on all of us. I kept running, soaking it up, past more people and past the lodge until I reached the sign I'd been looking for.

I was disappointed to find the hut at the trail head deserted. I wanted to talk to my three friends.

The rocky access road leading back to the parking lot seemed much longer now than it did this morning.

The clothes I'd left hanging on my bike were still damp. I put on my last dry shirt, and the rain jacket that had been in my backpack all day. I held my breath and ducked into that putrid toilet one more time.

Then I rolled away, down the long forested road where I'd see wild monkeys and think about my next hike. About how far I could go. About how long I could run.

Because there is so, so much to see.

No comments:

Post a Comment